The millions of Gaiman fans who have been waiting for an adult novel since 2005’s Anansi Boys will go crazy for this. The plot follows a man who goes back to his childhood home in Sussex after returning there for a funeral.

He has a nostalgic pull toward the Hempstock property, where three generations of fascinating and powerful ladies had resided. Lettie, the youngest, used to refer to their duck pond as her “Ocean,” which is subsequently revealed (in a wonderful passage) to be a metaphor for what could be called the cosmic life force.

The narrator, now an adult, recalls the magical and horrific events that occurred to him as a young boy of seven, and he does so while sitting by this Ocean.

Read Also:

- A Journal for Jordan: A Story of Love and Honor

- How Old Do You Have To Work At Dollar General

- All Things Possible Setbacks And Success in Politics And Life

Contents

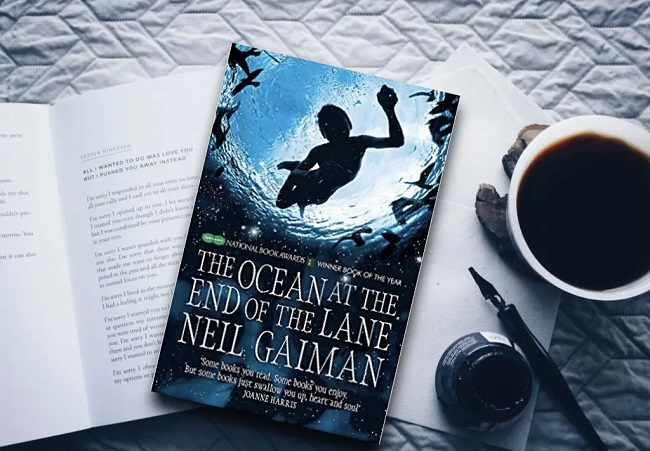

The Ocean at the End of the Lane Analysis

When the hero wakes up with a coin lodged in his neck, things get rather scary. He and Lettie go to the older two Hempstock ladies, who caution them to be careful when they attempt to “bind” the malevolence.

They find the monster out in the fields: “some kind of tent, as high as a rural church, built of grey and pink canvas that flapped in the gusts of the storm wind… a lopsided canvas structure aged by weather and tattered by time.”

As the two of them struggle, the narrator loses grip on Lettie’s hand and she continues to chant the binding spell (though these Hempstocks don’t name them spells: “Not that Grandma agrees with any of that. As she puts it, it happens frequently “) the creature inserts a worm into the narrator’s foot, namely the arch.

The young boy eventually manages to get the worm out, but not completely. The evil lingers and takes the appearance of Ursula Monkton, the narrator’s malevolent live-in nanny, a tall blonde woman dressed in a torn grey and pink frock that flaps.

Things have gotten really serious. And the only thing that scares Ursula Monkton, the only thing that will destroy this kind of monster, are the ferocious “hunger” birds…

As you might expect, I find the whole thing a little bit tacky, what with the flapping tent monsters and the worms in your feet and the gorgeous governesses. That wouldn’t be a problem (and isn’t, in terms of those millions of admirers), except that I find Gaiman much more engaging as a writer than this somewhat laboured “mythic” plot allows.

In order to clarify, allow me to elaborate.

On page 71, he begins to write his manifesto in the first person, using the narrator’s voice “Legends always fascinated me. These tales fell between the cracks of being either appropriate for adults or young readers. They were far superior.

Everything was how it was. The plots of adult novels never made any sense, and they were always a little slow to get going. It felt to me like I was being let in on some sort of masonic, mythical secret to entering maturity.”

Much of the book is built around this tired defensive argument – “In adulthood, people tend to stick to established routes. Typically, kids are curious and like to go on adventures.”

The moment in which the narrator’s father bursts down the bathroom door and dumps the scared youngster into a frigid bath while holding him under water is, in my opinion, the most impressively Realised and devastating.

Look at the way the Terrifying Realism is Hammered Home:

“I observed the serious expression on the father’s face. His outfit consisted of a sky blue shirt and a paisley-patterned tie in maroon. He unbuckled his watch and tossed the extendable strap on the sill.” Look at how well Gaiman has captured the harsh paternal figure.

Time slows down as the narrator takes in all the specifics, including the character’s “intent look.” Moreover, the watch being taken off so methodically and deliberately was a masterstroke; it evoked the cool, calculated demeanour of a torturer poised to begin his or her work.

And in a matter of moments, the kid will grab hold of that maroon paisley tie, “gripping it for life… lifting [himself] up out of that icy water,” holding on so tightly that his dad can’t push him down and drown him, and then he’ll “clamp” his teeth into it, right below the knot.

We take in the scenario, accept it at face value, live through it ourselves, and most of all, feel what is happening. Also, it’s very scary. That’s why; it’s the truth. There will be no supernatural nonsense, such as ghosts or monsters, or any phoney attempts at explaining anything.

Read Also:

- I ll Give You The Sun Summary

- How Far is Uvalde From San Antonio

- What Does The Feeling is Mutual Mean

Conclusion

That is to say, in the opinion of this reviewer, Gaiman’s knowledge and skill as a writer are best utilised in the grownup writing he claims to shun: his description of genuine human drama, relationships, sensibility, emotions, and thought.

And so, I’d love it if, one day, he’d stop with all these ragged tent-presences and just open his veins to write something profound about human beings, like dads and sons, without all the “gee-shucks-aren’t-the-adults-dumb” prophylactics.

However, I am cognizant of the fact that I may be completely alone in holding such a belief. Thanks for read our Article The Ocean at the End of the Lane Analysis.